In 1964, Omero Catan became the first person to cross the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, a bridge which, at the time, was the world longest suspension bridge, spanning 2.2 miles in length between Brooklyn and Staten Island in New York City, across the Narrows Strait which had welcomed the European explorer Giovanni da Verrazano 400 years earlier. Catan obsessed about the notion of being “the first” the first person to make use of the new public works projects which began to define the era of New York in which he lived in. Throughout the growing New York-New Jersey metropolitan area, Catan showed up to be the first in line after numerous ribbon-cutting ceremonies. He paid the first tolls on the New Jersey Turnpike, put the first coins into the first public meter facility in Hackensack, NJ, and made sure his car got the first New Jersey Car Inspection. He began his Mr. First career after being inspired by a family friend, William Goebbel, who had been the first person to cross the Brooklyn Bridge, the first great engineering feat of the Modern Era.

Catan had been living in the same age where the corruption that reigned in New York City, well before the Brooklyn Bridge was erected, and began to finally wash away in a flood of money for public works projects throughout the city, being headed by responsible leadership.

“I attend everything of civil interest which tends the furtherness of the pursuit of happiness, especially of the citizens of New York City and New York State.” (New York Sun, 1936)

What must be that atmosphere, the general mood amongst a population, which inspires and creates such an individual as Omero Catan? He embodied a certain faith in the Modern Age, where building was not merely intended to attest to greatness, but was built with good intentions, with the man hours of people who had previously been desperate for work and pay during the Great Depression, with a thought inside people’s heads that when times are down, we can come out as long as we support progress towards our future, and build infrastructure for the common good.

From the Great Depression, Franklin D Roosevelt acted on a new responsibility for government; to make the country string again by investing in itself, in public work. Catan took his obsession, inspired from Goebbel, and focuses it by becoming the point of attention at the first moment such public work became opened to have its merits tested and approved by the people. From the moment between The President of the United States putting his New Deal into action, to the moment that Omero Catan took the first trip over the last great public works project in New York City, the Verrazano-Narrows, there had been one man turning money into concrete, steel, and asphalt. The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge became the keystone in the edifice of the career of Robert Moses.

In the 1950s, Robert Moses beat a path along the coasts and shores of Long Island and New York City. In coastal Long Island, road and highway construction had been easy. By applying and fine-tuning his land acquisition tools which he honed in the great grab for state parkland in Upstate New York, Moses turned private land into parkland, and then simply altered the formula, substituting parkland for parkway land.

In New York City, road construction proved more difficult, for the land being turned into expressways was not simply private land, but neighborhood land. Three years before the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge opened, New York City put into effect the 1961 New York City Comprehensive Zoning Resolution, where the City Planning Commission and Department of Buildings saw areas of the city not in terms of neighborhoods, but in zones of usage, usage being permitted under the law. Much like a farm, where large tracts of land are designated and differentiated by the crops intended to be grown and harvested within each district, zoning designated what types of building will be built, and at which point must the alteration of existing non-conforming buildings bring such buildings into compliance with the latest approved zoning.

By the time New York City opened the Verrazano-Narrows, the city had finally mapped out and zoned every piece of land within New York City. For thirty years before hand, the city had seemed to give itself unto Robert Moses, as he forced his own lines across the fabric of New York City, acquiring land with the power of two words, “public good.”

At the heart of the Verrazano’s own construction lies the results of one of the government’s reserved powers; eminent domain.

It was the power which Robert Moses could use, not by being an elected official, but simply because he always had the plan in the drawer, ready to be pulled out, and with all the necessary actions noted and understood, with the precision of an engineer. Because he knew what would solve a problem, and how to execute the solution, Moses acquired power through the blessing of elected officials. Robert Moses had altered the way which the government acquires and makes use of public land, while the City of New York altered the way in which the privately owned land was used. The City of New York had created an anatomy of the city, noting its arteries, its nerve organs, its ports for import and export, and its designated areas of growth, its muscle, and support.

With the opening of the Verrazano-Narrows, Omero Catan crossed the bridge knowing full-well that he was the first blood cell to travel through the now-completed body of the City of New York.

The City prepared Staten Island with a plan for its growth and development by completely altering the rules for which Staten Island previously existed. With traffic now being fed from New York City and New Jersey, via the Staten Island Expressway, Staten Island went from rural community and beach resort to Suburban New York City. To spur the growth, Robert Moses had a plan, as he had for every part of New York State. For Moses, the end was not to be at the Verrazano-Narrows. The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge represented the greatest hurdle in a much greater dream of Moses, which had begun in Long Island. This dream was to drive uninterrupted along the entire Atlantic coast of New York State. Logically, a linkage of some sort between Brooklyn and Staten Island would thus become necessary, for which an expressway along coastal Staten Island would become the final step in the solution to the Shore Front Drive problem. Staten Island needed an expressway along its coastal beaches, to link up with the Richmond Parkway, and take people to the Outerbridge Crossing, which would take people down the coast of New Jersey along the Garden State Parkway.

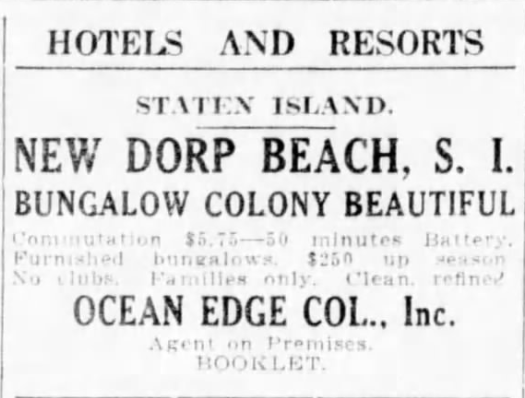

Staten Island, in the eyes of Moses, was merely a bridge to New Jersey, with land available to turn into parkway land. The plan was the Shore Front Drive, an expressway stretching from the Verrazano-Narrows, and going through South Beach, Midland Beach, New Dorp Beach, Oakwood Beach, and to Great Kills, where it would turn away, and meet up with the Richmond Parkway. With the onset of the Depression, the spirit that had made the beaches of the souther shore of Staten Island had left, with the remains of the amusement parks and boardwalks of the private land holders sitting, and allowed to go into the hands of the City of New York, in favor of new parks.

It was not a matter of re-imbursement for the property exchanging hands, but a matter of imposing drastic and immediate change upon areas of land, embodied by Notice of Eviction. The Shore Front Drive came right to the doorsteps of residents of New Dorp Beach, when their residential private land was transferred into the hands of the city for public assignment, that assignment being to build the Shore Front Drive.

The St. John’s Guild acquired the property for Seaside Hospital in 1879. The hospital held 275 beds, and was complimented by a seventy-six room nurse’s station, a superintendent’s house, and other buildings. The hospital went up for sale in 1951, according to a February 11th classified ad in the the New York Times. The site was 14 acres.

Next to the hospital sat the New Dorp Beach Hotel. Our Lady of Lourdes fronted Cedar Grove Avenue, in front of the hospital site.

At one time, New Dorp Beach received people on its beaches by boat. Hotels housed temporary guests. Bungalows houses vacationing families. Stores stood along either side of Cedar Grove Avenue. The oldest building on Staten Island stood at the corner of New Dorp Lane and Cedar Grove Avenues.

The site in question used to be active. There were structures and buildings of different uses interacting with one another.

Over the past twenty years, the city has only acted upon the site in question as a response to trash and fire. Stolen cars would be driven into the woods, stripped of all their parts, and then lit on fire. Roads used to lead into the beach area behind Our Lady of Lourdes Church, to the former site of the Seaside Hospital at St. John’s Guild. Four wheel drive vehicles could park along the shore, on the beach. Old streets still had their access to cedar Grove Avenue. The City of New York’s stop-gap measure was to place large wooden piers, to act as bollards, and limit the access to the site to bipeds.

How does an architect search for new potential uses in a community for a site which will not change?

The site in question teaches about the past. In searching the past of the site, the ghosts of former uses, and of former dreams return to haunt memory, influence program, and inform the future.

The question, thus becomes, what happens to the existing built form, when put face to face with the realities of the government? How does architecture react, respond, that is, what operations are applied upon land and its built form in response to newly given designations? The operations only occur when land is under development.